At the conference in Banff I met several indigenous Canadians, one of whom put me into contact with a widely respected elder of the Blackfoot nation. Someone told me later, “He wouldn’t tell you this himself, but this guy is one of most respected and influential elders in North America.” I really can’t say anything myself as to the state of politics among indigenous people of North America, but I can say that I highly trust my source that told me to trust this source.

The bottom line is I leveraged some networking at the conference I presented at to schedule a high-profile interview to teach me about the healing practices of indigenous Canadians. The day after the conference I drove up to Calgary for the interview.

I should clarify my terminology here at the outset. You may hear many different terms used to name the group of people who are the Canadian equivalent of “Native Americans.” Saying it that way is of course a bit odd, because the point is since these people are truly the “natives,” they predate the existence of Canada or America, and so that distinction of “indigenous Canadian” versus “Native American” is actually pretty meaningless. The benefit of that, though, is that by talking to this elder, I learned things that apply to the healing practices of many of the indigenous people across North America, at least at a high level.

After speaking with several people at the conference, it seems there is no general consensus on the term preferred by First Nation/indigenous/aboriginal people in Canada. Those terms are generally created and often changed by the Canadian government, I was told. Opinion varies between individuals as to which term is most appropriate. At this point, “Indian” is inaccurate, and “indigenous” doesn’t bother anyone, so that’s what I’m going to go with.

The protocol for asking to talk to healers has been different in each country. In Canada, if you are going to ask an elder for anything, traditionally you are expected to present them with tobacco. If they accept the tobacco, they have made a pact and are required to fulfill their end of the deal.

I found it odd that I had to present someone with a cancer-inducing agent in order to talk to them about how they heal people, but the reason is because this is rooted more in the traditional healing practices. Tobacco the plant, by itself, is one of the four sacred medicines of indigenous healing, along with cedar, sage, and sweetgrass. Historically, tobacco wasn’t usually smoked except for maybe special occasions.

Canada is a clean and beautiful country. Because of this, I had to withstand an absurd amount of judgment and attitude in the process of buying tobacco despite the fact that I have never smoked anything in my life. The people whom I asked who did not smoke gave me dirty looks and, regardless of how obese they were, were outwardly appalled that I’d do something so terrible for my body. And then when I did finally find someone who sold tobacco, he treated me like an idiot because I clearly had no idea what I was talking about.

The sacrifices I make for knowledge… In the end, I successfully obtained the cancer sticks formerly known as spiritual medicinal herbs and the elder accepted my offering, thus I have content to write about in this post.

I also did some research prior to the interview and was pleasantly surprised to find sites like this one that quite directly spell out the general healing philosophy, theory, and techniques of indigenous people in North America. It was not nearly as easy to find any of that information about sangomas or Aboriginal Australians.

The problem was, as I learned during the interview with this elder, that it was almost too easy. Or rather, the information was stated too concretely and too directly. None of it is “wrong,” necessarily, but there’s so much more nuance and so many context-dependent elements to this healing tradition that it is very difficult to describe in anything that resembles a textbook or scholarly report.

One of the first things the elder said to me in the interview was “I will be responsible for what I say, but not your interpretation of what I say.”

He elaborated, “In my language, the same sentence, the exact same words, can mean ‘it is cold outside’ or ‘I am at Dairy Queen eating an ice cream.'” There is an inherent limitation in discussing indigenous North American healing in English, because the English language defines words much more concretely than the languages of the people who practice these healing techniques. In fact, they don’t even have or use the word ‘healing,’ according to this elder.

For this reason, in the rest of this post I’m going to use as many direct (by which I mean paraphrased/later-reconstructed-from-memory) quotes as I can from the elder. I’ll clarify where I feel necessary and try to provide the context in which I was told these words. But I think the best way to represent indigenous Canadian not-healing would be to let the elder speak for himself and for me to avoid my own English language interpretation of his words as much as possible.

An ‘elder’ is someone who the community identifies as an elder. You don’t self-proclaim as an elder. Elders have earned the right to conduct ceremonies. Not just anyone can do them.

We don’t call it ‘healing.’ We don’t have healers. Don’t give me credit for what I didn’t do. You are not healing someone. Only the Creator heals someone. You are doctoring someone. You don’t call an M.D. a healer, you call them a doctor. And when you see them, hey don’t ask “are you healed” but rather ‘how are you doing today?’

The greatest teacher is nature. It will teach you things you don’t even think about. Have you ever heard an oak tree argue with a pine tree? Have you ever heard a pine tree tell an oak tree how to be an oak tree? Exactly. So how can we tell each other how to live our lives when we’re all so different?

What I can say, factually, or at least I can say factually that the elder confirmed these concrete ideas to me in person, is that they don’t use the word “shaman.” Elders who have earned the right to perform the sacred doctoring ceremonies will run them. You don’t go to medical school or anything like that. There is no degree. A person receives these ceremonies when they ask for them. The elders or community don’t decide for you that you need a ceremony.

The healing is holistic. It’s about centering the person. Every ceremony has a spiritual component to it. Cures and wondrous recoveries through ceremonies would be considered miracles by many. Indigenous Canadian people consider them to be spiritual, but we don’t consider them to be miracles because we expect them. We have faith, so we are not at all surprised when the spiritual ceremonies work, so we don’t consider them to be miracles.

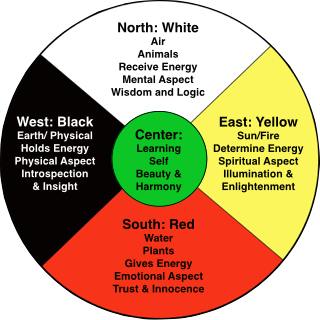

If you do any research as I did on indigenous Canadian healing, besides a description of the four sacred herbs I already mentioned, you will often see a description of the “medicine wheel.” It looks and is described similarly to the Wu Xing elemental model of Chinese medicine. There are the four directions of the wheel, (and you’ll read how the number four is a very significant and sacred number) each of which has a color, an animal, etc. And each direction is representative of one of the four areas – physical, spiritual, emotional, mental.

This is where, again, none of that is technically wrong. The descriptions of some of the specific ceremonies such as the sun dances or sweat lodges are mechanistically accurate, so I am posting this link again because it is very good for a concrete description of what some of these ceremonies might “look like” to a third party observer. But this is where the elder explained things aren’t so regimented as they are in allopathic medicine.

Yeah, the number four is special. But so is seven, nine, eleven, and thirteen.

There is the circle of life. It represents the spiritual, mental, physical, emotional. What does it even mean to have a balanced life? The circle is constantly moving and life is constantly changing. Balance is like having two identical buildings with a tightrope between them. If you walk out on that tightrope, you are balanced. But if you make one mistake it’s fatal. Balance is like being on one of those roundabouts on a children’s playground. If you’re living a ‘balanced’ life you are spending your time hanging on to the edge. And as it goes around you are spending your time in different parts – mental, emotional, physical, spiritual. But if you get tired you will fly off.

It’s about being centered. When you are centered you can admit to your own mistakes and learn from them. When you are centered, it’s OK to make mistakes. We all make mistakes. But most of the time we do things right. How often do we choose to focus on each, in ourselves, and in others?

How long would you say would be a good lifespan for you? 80? What if I told you that all of us have the exact same amount of time for each life, and that is one day. Today you have been given a life, and that’s all you have. Because yesterday is gone, and no one can guarantee me that they will be alive tomorrow. The past is for learning from but not living in, and the future is for hope, but hope based on the decisions you make today, not the ones you made yesterday.

It’s not about ‘what’s wrong with you,’ but rather, ‘what happened to you?’ And what is going on around you that is causing you to act this way or affecting you this way? What caused you to fly off the edge?

A large component of the process is people praying for each other. The elder or whomever is conducting the ceremony will pray and receive from the spirits the information of the treatment to pass on to the person. But you would still do the prayers and ceremony with the medicine you are taking.

The mechanics of a ceremony are almost irrelevant. To really know what happens in a ceremony you have to experience it. It’s between the individual and the Creator, whatever you may call the Creator.

The ceremony is you. Life is a ceremony. The ceremony is what’s going on inside of you during the sweat lodge, not the mechanics around it. Don’t thank me for what I didn’t do. Only the Creator can heal, and we are never really done healing. We are only done healing after we die and go to the spirit world and the healing becomes real. We are all on a path to wellness, but we are not healing.

Do you have any younger siblings? When your younger brother was sick, what did you do? Your mom was the primary caretaker. But you were sympathetic, maybe your dad was sympathetic, you weren’t necessarily the primary caretakers but you were aware and felt bad or had good intentions for him and adjusted your lives accordingly, maybe helped out a little bit. Is that not a ceremony?

He told me a lot of different anecdotes about his experiences with ceremonies. We talked about the integration of traditional and modern health care in Canada today. I have a lot more short, very specific quotes written down in my notes, which I’d be happy to talk to people about. But in an attempt to capture the meaning of (I believe) he was trying to say, I’m going to spare a lot of the specifics and odds and ends.

Before I left, he gifted me with some braided sweetgrass and taught me how to smudge, which is a cleansing ceremony that involves burning bits of the sweetgrass.

This was another one of those awesome conversations that, like so many moments this year, left me with a lot to process. I went back to my hotel, jotted down a ton more notes to remember as much as I could, and took a very needed nap.

2 thoughts on “Indigenous Canadian “Doctoring””